WASHINGTON: The Defense Department’s 2022 proposed budget appears to signal a shift toward funding more defensive cybersecurity measures at the cost of some offensive cyber operations.

The single biggest reduction in proposed year-over-year cyber funding appears to be in overseas “hunt-forward” cyber operations, with a $284.4 million cut to $147.2 million in 2022 versus a requested $431.6 million last year.

Comparing the 2022 request to the 2021 request reveals a few notable funding shifts:

- A new line item for implementing zero-trust architectures.

- Increases for zero-trust security enabling technologies, including cryptology, identity and access control management (ICAM), and automated continuous endpoint monitoring (ACEM).

- A decrease in funding for overseas “hunt-forward” cyber operations.

- An increase in Cyber Mission Force teams by four.

What does this portend?

Implementing Zero-Trust Architectures

The 2022 budget requests $615 million for “imbedding” zero-trust architectures.

As BD readers know, the US government has made a major push to promote zero-trust security. During a recent interview with BD, NIST scientist Oliver Borchert noted that zero-trust security “is not one single product that one can purchase off the shelf.” Instead, Borchert’s comments reiterated NSA’s characterization of zero trust as “a security model, a set of system design principles, and a coordinated cybersecurity and system management strategy.”

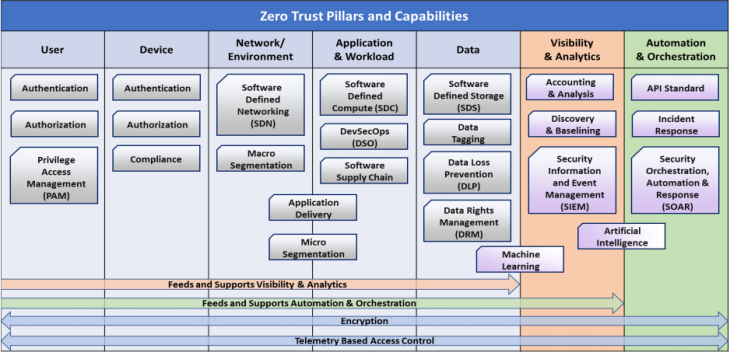

What does zero trust look like in practice? The zero-trust model is detailed in a new, 170-page document recently released by DISA. DISA’s Zero Trust Reference Architecture complements publications on zero-trust security previously published by NIST and the NSA.

To illustrate the zero-trust concept, DISA’s doc includes a graphic (below) in which security capabilities are mapped to the assets that must be protected, as well as security operations tools (i.e., visibility and analytics, automation and orchestration).

Source: DISA

It notes, “While straightforward in principle, the actual implementation and operationalization of Zero Trust incorporates several areas which need to be smartly integrated. …Implementing Zero Trust requires rethinking how we utilize existing infrastructure to implement security by design in a simpler and more efficient way while enabling unimpeded operations.”

And, the DISA doc says, “Apart from the advantages to securing our architecture in general, there are additional cross-functional benefits of Zero Trust regarding cloud deployments, Security Orchestration and Automation (SOAR), cryptographic modernization, and cybersecurity analytics.”

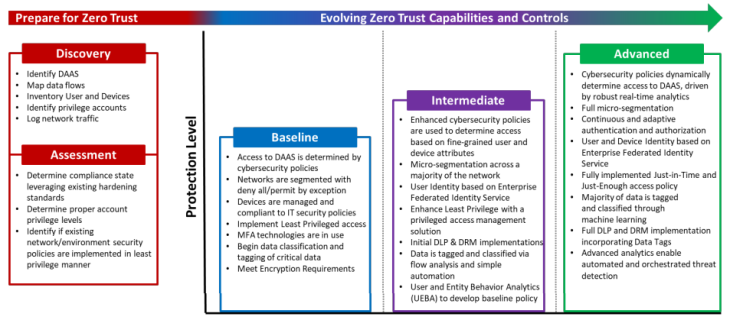

But the DISA doc is also realistic about the challenges of moving to a zero-trust architecture. It therefore provides a graphic illustrating zero-trust maturity levels, along with the necessary steps organizations can take to begin implementing this robust security model.

Source: DISA

Implementing zero-trust models will be a journey through multiple stages for most organizations, not a one-step process. And key to zero trust’s successful implementation will be tying together several enabling technologies into an integrated architecture.

Zero Trust Enablers

The 2022 budget includes significant funding increases for several zero-trust enabling technologies.

As NSA Executive Director Wendy Noble noted in April: “The zero-trust model is predicated on encryption algorithms and key exchange processes that are quantum resistant. Likewise, fine-grain, cross-domain management of authorities and access controls must be embedded throughout the architecture.”

Noble’s viewpoint is reflected in the budget request, which includes:

- $980.9 million for cryptology, an increase in the request of $302 million year over year, which appears to be the single largest increase.

- $243.9 million for ICAM versus a requested $198.5 million in 2021.

In addition, zero trust requires continuous monitoring, a move toward establishing anomalous behavior detection, and significant security automation, as reflected in DISA’s Zero Trust Reference Architecture and NIST’s Special Publication 800-207 Zero Trust Architecture.

Speaking at the Billington 5G Security Summit earlier this year, Gen. Keith Alexander, who previously led CYBERCOM and NSA, noted the need to “chang[e] the mindset and approach to what we’re doing. By anybody’s standard, cybersecurity’s not working. We’re not defending. We’re not even close.”

This change in mindset and approach includes, in Alexander’s view, a move from “static” to “dynamic” cyber defense, which entails what Alexander calls an “automated defense capability.” An element of this capability will be provided by ACEM, which the 2022 budget proposes funding at some $272.5 million more than requested in 2021.

“Hunt-Forward” Cyber Operations

The single biggest reduction in proposed year-over-year cyber funding request appears to be in overseas “hunt-forward” cyber operations, with a $284.4 million cut to $147.2 million in 2022 versus a requested $431.6 million last year.

CYBERCOM and NSA chief Gen. Paul Nakasone has said “hunt-forward” includes “executing operations outside U.S. military networks.”

Hunt forward is usually characterized as offensive in nature and falls under the doctrine of “persistent engagement,” which can mean retaliatory or preemptive cyber measures taken against adversaries to protect the US. “Persistent engagement,” Nakasone has said, “focuses on an aggressor’s confidence and capabilities by countering and contesting campaigns short of armed conflict.” Persistent engagement was formalized in DoD’s 2018 Cyber Strategy.

In congressional testimony this spring, Nakasone has referenced hunt-forward operations in support of the 2020 elections, saying CYBERCOM conducted “11 hunt-forward operations in nine different countries for the security of the 2020 election.”

Of course, DoD can be notoriously vague about cybersecurity — especially offensive cyber operations — so it’s difficult to know what, precisely, these operations entailed and who they targeted.

The shift in funding from hunt forward operations appears to reflect prioritizing more defense at the expense of some offense, especially given the slew of cyberattacks over the past few months — from the SolarWinds and Microsoft Exchange Server to Pulse Connect Secure hacks. Notably, none of these cyber campaigns appear to have affected DoD networks directly, although they reportedly affected several federal agencies and the defense industrial base.

Or it could be funding for hunt forward is being shifted to another line item, such as expanding Cyber Mission Forces.

Expanding Cyber Mission Force

One of the biggest questions right now about the proposed 2022 cyber budget revolves around this expansion of the Cyber Mission Force.

According to the 2022 and 2021 budget documents, existing CMF teams include:

- 13 National Mission Teams to defend the United States and its interests against cyberattacks of significant consequence.

- 68 Cyber Protection Teams to defend priority DoD networks and systems against priority threats.

- 27 Combat Mission Teams to provide support to Combatant Commands by generating integrated cyberspace effects in support of operational plans and contingency operations.

- 25 Support Teams to provide analytic and planning support to National Mission and Combat Mission teams.

Details on the role, composition, and costs of the four new CMF teams are sparse in the budget document, although it does note “additional funding and civilian manpower, and adjusts military manpower.” The document also notes the four teams will support “increased cyber operations” and provide cyber support for space operations. The specific type(s) of cyber operations (i.e., offensive or defensive) to be supported by the new teams is not detailed. Support for space operations, which is equally vague in the budget document, can reasonably be interpreted as more defensive than offensive.

It’s possible the apparent cut to offensive operations in the “hunt-forward” line item is merely being transferred to some of these new CMF teams, while providing a level of strategic ambiguity to adversaries — who can, of course, access and analyze published budget documents — on the focus of US operations going forward.